The Punjab government’s announcement of relieving Dr. Faisal Masood from his additional charge as Chief Operating Officer/Medical Superintendent of Mayo Hospital was presented as a decisive move against mismanagement. Yet, the reality tells a different story—one that exposes not just the government’s performative governance but also how Maryam Nawaz has once again been misled by the very bureaucrats she claims to be reforming.

Dr. Masood had already resigned from his position on February 12, 2025, citing personal reasons, yet his “removal” was dramatically announced nearly a month later on March 6, just days after Maryam Nawaz’s hospital visit. The question is not whether he deserved to stay or go—the question is why the government staged this entire episode as a public spectacle when his resignation had long been on record. If the chief minister was aware of his resignation, why the deliberate delay in making it public? If she wasn’t aware, then who in her administration fed her this scripted action, setting her up for yet another reactionary, optics-driven decision?

Punjab’s bureaucracy has long mastered the art of manipulating political leadership into taking superficial actions that maintain the illusion of reform while ensuring that real power—and real accountability—never reach those actually responsible for institutional failures. Instead of addressing the deeply embedded problems plaguing Mayo Hospital, the government chose the easiest, most media-friendly solution: remove a single individual, frame it as a bold move, and let social media do the rest. But does this removal fix the corruption, mismanagement, and systemic failures that have left public hospitals in crisis?

This is not the first time Maryam Nawaz has fallen for such bureaucratic deception. Since assuming office, she has consistently relied on high-profile visits and media-driven crackdowns, yet her administration remains plagued by reactionary decision-making rather than structural policy changes. The same bureaucrats who failed previous governments remain firmly in control, feeding her pre-packaged narratives that allow for headline-worthy dismissals while shielding the real powerbrokers. If anything, this episode underscores who truly controls Punjab’s governance—and it isn’t the elected officials.

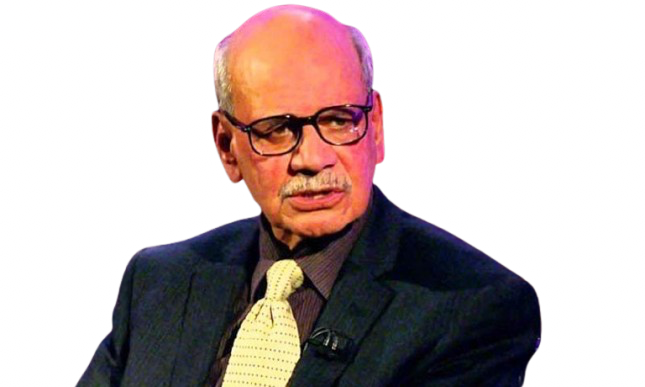

However, there is one recent example of a leader who refused to be played by the bureaucratic elite—Caretaker Chief Minister Mohsin Naqvi. Unlike his predecessors, he did not fall for staged theatrics or knee-jerk decisions. Instead, he streamlined governance, took tough but necessary actions, and exposed bureaucratic inefficiencies rather than becoming their pawn. His tenure demonstrated that it is possible to govern effectively without being manipulated into superficial moves designed for media optics.

Mohsin Naqvi’s approach to hospital reform was not about media stunts but about real, measurable change. Under his leadership, the Punjab government increased funding for emergency wards, launched a crackdown on ghost employees in hospitals, upgraded medical equipment in major public hospitals, and initiated a merit-based hiring process for doctors and paramedics. He prioritized the digitization of hospital records to curb corruption and pilferage, ensuring that medicines actually reached patients rather than disappearing into black markets. Most importantly, he did not rely on symbolic dismissals but held entire hospital administrations accountable, creating a system of oversight that put pressure on officials to deliver real results.

If Maryam Nawaz wants to avoid being remembered as a leader who simply reacted to scripted crises, she must learn from Mohsin Naqvi’s ability to outmaneuver bureaucratic games and focus on genuine institutional reform. Instead of playing into the hands of those who stage-manage governance for optics, she must demand long-term structural reforms, hospital audits, and a sustainable policy framework that prevents such crises from recurring.

The deeper issue at Mayo Hospital—and across Punjab’s public health sector—goes beyond one man’s appointment. It is a crisis of chronic underfunding, political appointments, procurement corruption, and administrative inefficiencies that cannot be resolved by simply scapegoating individuals. The real test of leadership is not in orchestrating symbolic removals but in dismantling the entrenched bureaucratic networks that have turned public institutions into fiefdoms of inefficiency. Yet time and again, we see political leaders opting for theatrics over tangible governance.

Maryam Nawaz has a choice to make. She can continue being a pawn in bureaucratic power games, reacting to staged events designed to make her appear in control. Or she can assert actual authority, demand real institutional audits, and introduce long-term reforms that go beyond PR-driven dismissals. If she truly wants to be a reformer rather than just another figure in Pakistan’s cycle of performative politics, she must break free from bureaucratic manipulation and focus on governance beyond optics.

The handling of Dr. Masood’s removal was not a display of strong leadership—it was a scripted performance designed to sustain the illusion of accountability. Until Maryam Nawaz stops governing through spectacle and starts demanding substantive change, Punjab’s governance will remain in the hands of those who thrive on the incompetence they pretend to fix.